Sandals? In Scotland? The man was clearly deranged.

Image: Pixabay

There’s no more attractive sight than seeing a man in costume. Well, certain costumes. Not clown ones with massive feet and red noses and the whole scary white make up thing.

I was thinking more along the lines of historical costume. There were just certain periods in history when fashion got it right so far as accentuating the finer points of the male form goes.

A while back my husband went to a big work do. As the party was fancy dress and the theme Pirates, the staff were able to hire clothing from a stage costumiers and my husband came home with a beautiful 18th century style frock coat, complete with brass buttons and braid and breeches to match. And a tricorn hat. To say he looked dashing was rather an understatement. I tried to persuade him to hire it for an extra few days over the weekend, but he demured. Coward.

It’s not just 18th century costume either.

Anyone remember Blackadder? Course you do. Remember Rowan Atkinson’s transformation between series’ one and two? He went from a snivelling dweeb with a bowl haircut and an outrageous selection of positively aggressive codpieces in the first series to an Elizabethan gallant, all trimmed beard, black doublet and hose and pearl drop earring in the second.

Now, I’m sure no one would ever class Rowan Atkinson as a heart throb. One of Britain’s greatest comedy actors? Yes. Sexy? No. Not until he was strung into that black velvet. Or is that just me? (No – it’s definitely my mother as well.)

Which kind of brings me to this week’s Books in the Blood:

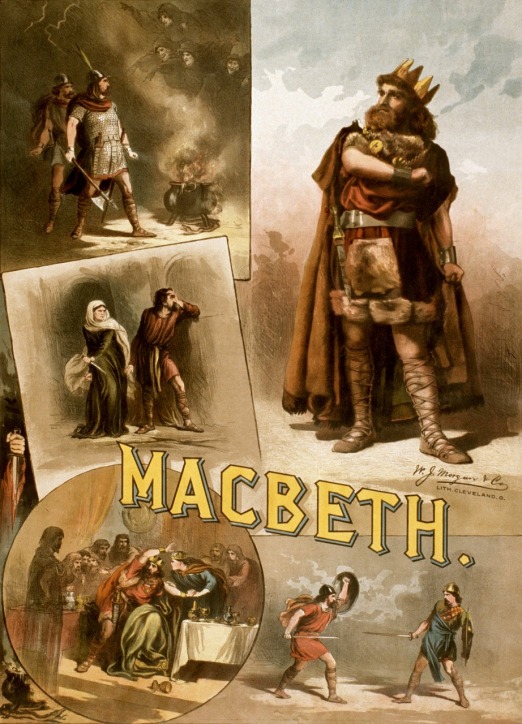

SHAKESPEARE PLAYS.

I loved Shakespeare at school – eventually.

But you see, people start the study of Shakespeare all wrong.

We’re introduced during those turbulent, troublesome teenage years, when your body’s like a chemistry set, a frightening jumble of hormones shaken together in all the right quantities to produce mental instability on a cosmic scale. And the way schools ease us into the works of the greatest British writer, with his themes of social climbing, cross dressing, regicide, suicide and murder, murder, murder is by showing us the text first.

Clearly, I get this. As a lover of words I know that what makes Shakespeare great, what makes him endure through four centuries and presumably into the distant future for as long as man exists, are his use of words, his prose and poetry, the way he describes the human condition.

I get this. But I’m not sure most teenagers do.

What teenagers get is difficult (occasionally impenetrable) language, loaded with Classical, mythological and medieval references they don’t recognise and jokes that just aren’t. They and their classmates have to take on roles, to read the text in class and if there’s anything less romantic than a self-conscious fourteen-year-old stumbling through

If I profane with my unworthiest hand

This holy shrine, the gentle sin is this:

My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand

To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss.

while his mates are laughing and lobbing spit balls at him, I don’t know what is.

But I have a radical solution.

Before teachers hand out text books, before teen eyes settle on a single letter of the great man’s work, before the kids have had the chance to feel bamboozled, flummoxed, lightminded or just plain bored by the Bard experience …

TAKE THEM TO A LIVE PERFORMANCE FIRST

Shakespeare wrote plays. Plays which were meant to be performed and watched and gasped at and laughed through. They were NOT meant to be read and analysed, line by line, couplet by couplet, in one hour chunks in enclosed, dusty classrooms with the lure of sunshine and break time taunting you through the window.

Let them feel that adrenalin rush of a live performance. Preferably take them to see a tragedy, because all that intrigue, sex and violence that accompanies Macbeth, Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet tick every box in the teen brain stem. Let them hear swords clash, see the actors stumble and spit their lines and argue and kiss.

The students won’t understand every line. They will miss some of the references. But they might just leave the theatre with an initial good impression of Shakespeare. Then at least when they do look at the texts they might remember that sword fight, that kiss. The text might make more sense and they might realise Shakespeare isn’t boring.

And as they plough through iambic pentameter, they might remember the dashing hero in the doublet and hose too.

Every time I discuss Shakespeare I share alink with Desperately Seeking Cymbeline – and today will be no exception.